This undertaking is to commemorate the 200th. Anniversary of my Gilmour family's emigration to Canada from Scotland. I commenced this project on January 9th, 2021, and as you can see, have now spent several months in its completion. I especially want to acknowledge the transcription work done by Charlie Dobie on The John McFarlane Journal; all of the help and assistance of Marilyn Snedden over many years, on maps, and various other topics; the additional data on our John Gemmill family from Fran Cooper; and to Karen Robinson-Foote for her investigation into the Lloyd's records of the ship "David", or "David of London", as to which name it was often referred.

I intend this story, not as a complete genealogical tome, but rather a narrative of what was probable regarding my four-times great grandfather's journey – leaving his former life behind, and opting for a new start, and better opportunities for himself, and his family, in a new land. So . . . some of the following will be speculative (although based on actual social conditions of the time), but most of it will be actual facts, as documented by historians and diaryists, who very fortunately for me, documented the actual sea voyage of their ship, and the over-land travel to their new home.

As an additional document to accompany this work, I offer a consolidation of my daily "blogs" sent out over the course of their journey, titled My Day-by-Day Account of their Journey from Scotland to Canada.

Background Information

Per Carol Bennett's book "The Lanark Society Settlers" (pages 122/123), 4 Gilmour families sailed together on the ship "David of London", in 1821, as part of the Glasgow Trongate Emigration Society. The "David" (captained by a J. Gemmill), a ship of 380 tons, sailed from Greenock, Scotland, on May 19, 1821, with 364 men, women, and children (from 10 emigration societies), and arrived at Quebec City on June 25 (recorded as a voyage of 33 days – BIFHSGO Pub. #1). See Appendix A for more detailed information on the ship "David of London".

Despite other researchers somehow arriving at a different date, I believe that John Gilmour was born in 1755, the son of Allan Gilmour and Margaret Anderson, who were married in August of 1754. Since his father was listed as a "Weaver at the Kirk" – probably in Neilston Village, Renfrewshire, it is quite possible that John also had spent some time as a hand-loom weaver of cotton before his military service. John served in the British Army, in the 21st. Light Dragoons, from 1778 to June 19, 1783, the date of his discharge. He married Ann Whyte on February 11, 1787, in Neilston Parish, Renfrewshire, Scotland.

The Gilmour family party, bound for Canada, was comprised of John Gilmour Senior (bc. 1755-d. 1846), his wife Ann Whyte (no definite birth or death dates for Ann), and 3 of his sons. The first son was Allan (b. Aug. 20, 1789; d. Jan. 5, 1868), who married Margaret Anderson on April 30, 1814, in Neilston Parish, Renfrewshire, Scotland. Allan and Margaret had with them 3 children: a girl b. 1815, a boy b. 1817, and William b. 1821. The second son was Hugh (b. Jan. 16, 1794; dc. 1872), who married Margaret Fallow on Oct. 26, 1816, in Neilston Parish. Hugh and Margaret had with them 2 daughters: Anne (b. Feb. 27, 1817), and Mary (b. Dec. 8, 1819). The third son was James (b. April 6, 1796; d. Feb. 8, 1891), who married Ann Cherry on March 20, 1823, by the Rev. William Bell, in Canada (so he had travelled as a single man from Scotland). John Senior's eldest son John (b. Oct. 30, 1787), was still serving in the British Army in the First Regiment of Foot, and did not come to Canada until 8 years later, settling in Huntley Twp., as all of the lots in Ramsay Twp. had been then been taken. John Junior had already married Jane Clark (bc. 1802) on July 16, 1826 in Paisley, Scotland. John Senior's son William (b. Jan. 1, 1792) is still a bit of a mystery, presumably also emigrating to Canada at a later date, but when and where he arrived is still uncertain. John Senior's daughter Mary (b. July 8, 1802, in Neilston Parish) may have come with them, (as suggested in the Donald Whyte book that John Sr. wife, and 1 child travelled together), but that has not been proven. John's son Andrew (b. Nov. 9, 1799) may have died before their emigration in 1821.

Preparations for the Sea Voyage

Prior to leaving Greenock, it seems that the heads of each family were responsible for ensuring that adequate provisions (as specified by legal regulations) were on board the ship. These were calculated to be sufficient for a passage of 84 days to Quebec City. These included:

- 18 pounds of Irish Mess Beef (@ 4 pence) = 6 shillings

- 42 pounds of Biscuit (@ 2 pence) = 7 shillings

- 132 pounds of Oatmeal (@ 2 pence) = £1, 2 shillings

- 6 pounds of Barley or Pease (@ 2 pence) = 1 shilling

- 6 pounds of Butter (@ 10 pence) = 5 shillings

- 3 pounds of Molasses (@ 4 pence) = 1 shilling

- Total Cost for Food = £2, 2 shillings

Passage costs to Quebec City from Greenock were – for each emigrant above the age of 14, £3 10s 0d, and for each child from 2 to 14, £1 3s 4d. These food and passage costs were either borne by the individual families themselves personally, or by the Societies, of which they were a member. Note that the Gilmour and Cherry family may have been independently funded.

The quantities described above had to be laid in for each individual above 8 years of age. Each child from 2 to 8 must have three-quarters of the above quantity, and each child under 2 years of age must have one-half of the above quantity.

So, one can imagine this extended family of 13 persons, packing up some of their worldly goods in trunks, and carefully wrapping smaller treasured objects in clothing, to protect them from breakage during the sea and land voyage. We can only speculate on what the majority of these items would have been, but given the Will of John Gilmour Sr., we can guess that some of these items were his 8-day clock (if permitted), his Family Bible, and 5 volumes of Henrey's religious commentaries (which were mentioned in his Will).

Part One: The Sea Voyage

John got involved with the Glasgow Trongate Emigration Society, and that is how he, his wife Ann, and 3 sons Hugh, Allan, and James came to Canada. His family and approximately 364 other settlers booked passage on the ship "David of London", which set sail from Greenock (near Glasgow, and from the East Quay), on Saturday, May 19th, 1821. Per John McDonald's book [page 3] ". . . I left Glasgow for Greenock, to embark on board the ship David of London, for Quebec, alongst with nearly 400 other passengers, where, having gone through the necessary steps at the custom-house, we left the quay on the 19th. of May 1821. A steam boat dragged the ship to the tail of the bank, and the wind being favourable we immediately sailed, and in 28 hours lost sight of land." (Note: Greenock is 25 miles west of Glasgow.) John McFarlane added in his journal, that after the steam boat brought the ship out at 4:00 p.m., "three tugs brought us clear".

Another (more detailed account) of the ship's departure was provided by an article in the Edinburgh Courant newspaper (per the British Newspaper Archives):

The "David" left Greenock about 1:00 p.m. on Saturday [May 19] with 364 passengers [bound] for Canada. She was towed out by a steamboat, and immediately proceeded to sea with a fair wind. The "David" was left by the owner and friends of the passengers about 2 miles below [south of] the Cloch Lighthouse, at 6:00 o'clock p.m. with 3 hearty cheers from the passengers and crew, which were immediately returned from the boat and repeated from the ship: a general smile of satisfaction closed this parting scene.

Photograph of the Cunard liner "RMS Carinthia" shown with the Cloch Lighthouse on the right.

Model of a ship similar to the David of London.

Above image of the ship, per Marilyn Snedden's book titled "The Robertsons of Ramsay", published in 2006.

On this same ship were other settlers who would figure in our family's story, i.e. John Gemmill (not the Rev. John Gemmill) coming alone, (his wife Ann Weir, and 7 children to follow a year later in 1822). See Appendix F for more information on John Gemmill Sr. and his family. One of these children, Janet Gemmill, would later marry Adam Craig, and in turn their son, John Gemmill Craig would marry Nancy Walker from Perth. Then, their daughter, Jannet Gemmill Craig would marry Charles Cash Gammons (in Hastings, Minnesota, U.S.A.), who would produce our grandmother, Rose Gammons, who would later marry Harry Dawson Gilmour in 1909.

Per Carol Bennett, other settlers on the "David" also part of the Glasgow Trongate Emigration Society were as follows, so, if John Gilmour and his family did not know any of these folks in advance, he certainly would have by the time they all reached Quebec City. I have indicated lone travelers with an "(I)" to denote "Individual", and a family of at least husband, wife, and one child with an "(F)" – John Baird (I), Robert Barclay (I), James Bowes Sr. (F), Alexander Bowes (I), James Bowes Jr. (I), John Bowes (I), Thomas Bowes (I), Thomas Deachman (F), Janet Drummond (I), Thomas Duncan (F), James Ferguson (F), John Findley (F), John Gemmill – the Merchant (F), John Gemmill the Stonemason (his wife Ann Weir and children were still in Scotland) (I) – this couple are my (Ken Godfrey's) four times great grand-parents!; John Gemmill (I) – born Catrine, Parish of Sorn, Ayrshire; Rev. Dr. John Gemmill – Presbyterian Minister and Medical Doctor (F), William Hamilton (I), Mrs. Hart (I), John Kent (F), William Kyle (F), William Laverty (F), David Leckie (F), John or James McAlpine (I), Malcolm McDonald (F), William Purdie Sr. – died enroute to New Lanark (F), William Purdie Jr. (I), Archibald Rankin (F), James Robertson (F), James Rollo (F), Peter Taylor (I), Hugh Wallace (F), James Watt (F) – his son John was one of the children who died on the "David" on its way to Canada, John Watt (F), Thomas Watt (I), Mrs. Hugh Wilson (F), James Wilson (F), John Wilson (I). Note: There were also passengers from nine other emigration societies on the "David" as well.

From Greenock, their ship would have sailed down the Firth of Clyde, past the Cloch Lighthouse, and then through the Sound of Bute, and the Sound of Kilbrannan, and past the Mull of Kintyre, which is the southernmost tip of the Kintyre Peninsula (which they passed on Sunday morning. May 20th). I then assume that the ship headed for Ireland, passing by its north coast.

By Sunday, May 20th. they were sailing with a fine breeze of 8 knots, and the wind continued on Monday, May 21st., sailing at 9 knots an hour. But, by Tuesday, May 22, the wind was coming from the SW, and "the most part were sea sick". Wednesday, May 23rd. the wind was at 4-1/2 knots, and a number of porpoises passed the ship. Thursday, May 24th., the ship lay becalmed, and there was a mutiny on board! Friday, May 25th. there was a fair breeze, and later it blew hard through the night. Saturday, May 26th. the wind is blowing very hard, and a child was born. Sunday, May 27th. there was very little wind, and it came from dead-ahead, so progress was slow. On Sunday, the passengers heard a sermon from Dr/Rev. John Gemmill, but a child died later that day.

But, then the weather turned very bad (confirmed both by John McDonald and John McFarlane's accounts). "The wind rose, a heavy gale commenced, and the waves rolled mountains high." – per John McDonald. "We now became like drunken men, reeling and staggering to and fro". McDonald goes on to explain that this severe storm lasted for 9 days, and even the ship's captain, John Gemmill (not to be confused with the Rev. John Gemmill, also on the ship), stated that he had never witnessed such a tempest of such long endurance at that time of the year! The violence of the storm caused the cooking pots to tumble down so that no food could be cooked, and they had to resort to eating oatmeal mixed with molasses. Many passengers got drenched by the waves breaking over the deck, and the water even entered the hatches, as many were confined below deck in the hold. At the start of this storm, the weather turned very cold, and this cold continued until the ship reached the mouth of the St. Lawrence River.

Now, picking up the daily detail from John McFarlane's Journal, it seems that the 9-day gale may have started later on Monday. May 28th, and lasted through to Tuesday, June 5th. During this violent storm, a child died on Tuesday, May 29th., another child was born on Saturday, June 2nd., and a third child was born on Monday, June 4th. On Wednesday, June 6th, McFarlane notes that the gale finally slackened, and on Thursday, June 7th. a second child died. He notes that on Friday, June 8th. they hailed a French Brig, and the next day on Saturday, June 9th. they saw another ship ahead of them. On Sunday, June 10th they passed a ship called the "Providence of Bournemouth" from Liverpool. She had been at sea for 20 days. Later, on June 10th. Rev. Gemmill preached another sermon.

McFarlane continues: Monday, June 11th, we are upon the Banks [i.e. the Grand Banks] off Newfoundland, with a cold, and heavy gale. But the next day (Tuesday, June 12th) the ship was becalmed, and the wind picked up the next day (Wednesday, June 13th) with a light breeze. On Thursday, June 14th, the passengers were treated to the sight of 15 vessels, and by the next day (Friday, June 15th) the "David of London" had passed most of them, so these 15 other ships must also have been on their way towards Quebec City. The next day (Saturday June 16th), the wind picked up to a strong breeze, but slackened off the following day on Sunday, June 17th to just a slight breeze. As it was Sunday, Rev. Gemmill preached his customary sermon, and the ship entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Perhaps how the "David" appeared in the heavy gale on June 11, 1821

Monday, June 18th. there was a slight breeze, and another child was born. On Tuesday, June 19th. the breeze freshened to 10 knots, and they now saw the coast of Nova Scotia on their left [i.e. south side], which appeared mountainous with some specks of snow on them [possibly Cape Breton], and Labrador on their right [or north] side. On Wednesday, June 20th. there was a slight breeze, and a child died of the croup. Thursday, June 21st. saw another day with a slight breeze, and they saw their first houses, about 8 in number and close together. Afterwards that day, they saw game on the shore, but at a considerable distance [possibly deer]. On Friday, June 22nd., McFarlane notes that the river is narrow, and they had a closer view of Labrador which appeared to be partly sandy along its shore. The south shore now had beautiful high hills covered in forests. They passed the Green Isle [possibly Prince Edward Island], with a lighthouse on its shore.

Now, being well into the St. Lawrence, and with the prevailing wind ahead of the ship, progress was much slower, but there was much more to see on the river banks as they passed upstream. We now switch to some more detailed account by John McDonald. When the ship entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence, it was necessary to obtain a pilot, to navigate the more difficult and potentially dangerous sections of the river. Now, as the weather warmed, the Captain ordered all of his passengers (including those sick passengers, with some assistance) to bring up their clothes and to air them out, as he feared that some infectious fever might result. But, those passengers recovered quickly, and the Ship's Surgeon happily declared that there "was no fever amongst us".

Since they were now heading into the wind, the rate of sailing was much slower, and hence the ship anchored several times, which was a joy to the sick passengers. On one such occasion, some of them were able to go ashore for the first time since leaving Scotland. However, despite the Captain's orders that no "ardent spirits to be brought on board", some of the passengers returned with rum, which was subsequently seized, and thrown over-board. This loss caused blows between the sailors and passengers (and even between some of the sailors!), and it was not until night time that the disorder abated.

The "David" arrived at Quebec City on the 25th of June, where they were all inspected by the surgeon, and then passed through the Custom House. They all slept on board that night, but by 6:00 a.m. the steam boat "Lady Sherbrooke" was alongside, and they started to move their luggage onto it, which took a good part of the day. The steam boat finally set off at 11:00 p.m., and almost immediately they were engulfed in a fierce thunder and lightning storm, with very heavy rain which drenched most of the 400, who were sitting on the deck exposed, and not in cabins. McDonald states that their being thoroughly rain-soaked attributed to some deaths later in their trip, and wrote "the beds of those passengers who were stationed on the lee side of the boat, between the engine-house and the paddles, were made literally to swim with the rain water". The journey to Montreal took 24 hours, a distance of some 190 miles.

The steamboat, the "Lady Sherbrooke" may well have looked similar to the above steamboat, the "Comet".

Model of the Lady Sherbrooke

The steamboat, the "Lady Sherbrooke" may well have looked similar to the above steamboat, the "Comet".

The sketch at left shows what the skeleton of the actual "Lady Sherbrooke" looked like. She was 40.7 meters long, and 9.5 meters wide. In Imperial measure, that would be 133 feet, 6 inches long, and 31 feet, 2 inches wide.

For more information, see Appendix I: Additional Information on the Steamship "Lady Sherbrooke".

Part Two: The Over-Land Trip – but Some by Boat!

Replicas of the batteau style of boats.

At Montreal, they had to move their luggage from the steam boat to a large number of wagons provided by the government, as part of their emigration scheme. Those unable to walk, climbed aboard these wagons, but the remainder walked to the village of La Chine, which was ten miles west of Montreal on the St. Lawrence River. They arrived at La Chine on June 28th., but had to wait there for 4 days, until they assembled as many boats as were required to move all of the settlers. Then, on July 2nd the 366 settlers set out on 15 flat-bottomed boats (known as "batteaux"). Or, possibly the flat-bottomed boats referred to were actually Durham Boats, since with 15 boats, each would have had to have held approximately 25 passengers each, to transport the 366 settlers.

Replica of a Durham boat in a Canal Lock at Lockport, New York.

Durham Boat showing side boards for Poling.

This was the beginning of the very difficult passage through many strongly flowing rapids. In many, the river was very shallow and stony, and the boats with their full loads grounded, necessitating that all the men jump into the river, and wading sometimes up to their chests, hauling the boats along. The women and children had to walk at these points. However, at some places, the current was too strong for the men, and two horses had to be obtained to pull every boat through successfully.

So, during this part of their journey, many of them were constantly wet, and unable to dry out. Some of the lucky were able to over-night in barns and farm houses, but, for the most part, they were forced to sleep outside by the river side, or in the woods. As McDonald wrote ". . . I have found in the morning my night-cap, blankets, and mat so socked {viz} with dew, that they might have been wrung." Thus, they spent 6 nights, travelling from La Chine to Prescott, a distance of 120 miles. Due to being almost constantly wet, and probably drinking contaminated water, many were afflicted with the "bloody flux" (which we today know as dysentery. Its symptoms are fever, intestinal hemorrhages, and diarrhea), and many died after a few days. This marked the end of their journey by water.

They had to stay in Prescott for 3 weeks, due to the "bottle-neck" created by passengers from previously-arrived ships waiting there for sufficient wagons to move them to the next stage. These were half the passengers from the "Earl of Buckinghamshire", all those from the ship "Commerce", and of course, all those from the "David of London" – 1,000 souls in all. Many had to remain there due to sickness, and many died. For example, William Purdie, an agent for the Trongate Society, died there. Previously, a Mr. Dick had drowned in the St. Lawrence River, while bathing, leaving his wife and 10 children to fend for themselves.

Note that, per Robert Lamond's book, (page 95) there is a letter dated June 30th, 1821, Quebec City, that William Purdie wrote to Robert Lamond in Scotland, describing something of his sea voyage, and making suggestions for future emigrations. He also refers to the journal he kept, which he still intended to send a copy of to Mr. Lamond, but in a fateful comment added "If I am spared to arrive." Therefore, had he lived, I, and other present-day researchers, would have had a third journal from which to draw important data.

McDonald goes on to describe Prescott as a fine little town, and growing quickly, as it was also a military station. However, he laments how little the Sabbath Day is respected here, with many "employed in singing, in playing on flutes, and drinking". They were there for 3 Sundays, and held church services in a school-house. McDonald also stated that most of the residents of Prescott, at that time, were French and Irish, and that the mail-coach stops there, this being the only road to Kingston, which is 62 miles away to the west.

Stage Coach – Chelsea, Quebec – 1885.

Finally, after their wait of 3 weeks, they left Prescott on Monday, July 30th. They travelled 6 miles that night, stopping at an inn, and arose at sunrise the next morning, travelling another 6 miles to Brockville, and had breakfast there. They stopped only one hour at Brockville, and then, leaving the St. Lawrence River behind, set off north through the country-side, stopping the next night at a farmer's house, and sleeping in the barn, fearing snakes! Each night they slept where they could – sometimes barns, sometimes stables, and on lucky occasions they were able to sleep on the floor of the horse-driver's home, when passing that way. (I assume that, at this point of their journey, they were travelling in individual wagons, and not as part of the large group that had been together before, as the road conditions, such as they were, would not likely have permitted a large group to travel together).

The baggage wagons could have looked similar to this one.

The journey continued, with frequent changes of horse and driver. The "roads" were deplorable, with mud and mire making their journey extremely arduous, and sometimes dangerous, as many wagons overturned, one boy being killed, several others hurt, and one man breaking his arm! At one point, a yoke of oxen was necessary to free a wagon from the mud. Several times, they had to pull down the farmers' fences, and use the logs to fill ruts in the road, so they could get the wagon through. But as they approached New Perth (now just called Perth) the roads improved, and the drivers invited some of the men to climb into the wagons, which they did with great appreciation!

McDonald describes Perth at this time as having 2 churches: one Presbyterian meeting house, and one Catholic chapel; 2 bakers, several store-keepers, 2 or 3 smiths [probably blacksmiths], and a post-office. The latter had a very long list of names attached to its door, indicating those for whom letters were waiting for pick-up. (Note: In many cases at that time, letters were sent without postage of any kind, and it was incumbent upon the recipient to pay whatever charge was due. According to Stephen Young in 1861, letters from Scotland cost 3 shillings and 6 pence. Unfortunately, many new settlers had no real money to redeem their letters, so probably many were never received or read, which is a real pity!)

They left Perth the morning after arriving (probably August 3rd.), and set off for Lanark, a distance of 14 miles. On their way, they had to ferry over a large stream, identified as the Little Mississippi [to distinguish it from the much larger Mississippi River of the U.S.A.] When they got to within 2 miles of New Lanark [as it was then called] on August 4th, they were informed that many of the settlers' health was getting worse, and in one case 4 from the same family were sick at the same time, from fevers and agues.

At Lanark, "housing" for the newcomers was described as either tents, or quite primitive structures of poles and branches of trees, sometimes covered with blankets in a vain attempt to keep out both the heavy rains, as well as snakes, squirrels, oxen, cows and pigs! They managed for a time in these conditions, while the men would go out to view potential settlement lots of 100 acres in the townships of Lanark, Ramsay, Dalhousie, and Sherbrooke, by way of "tickets" issued by Colonel Marshall, the agent in charge of land distribution.

There is, of course, no way of knowing for certain, but I am assuming that 3 weeks was sufficient time for all of the settlers to view their 2 lot choices, make a selection, and arrange to start building their Log Homes, in preparation for the impending Winter. So, with luck, and good management, most of these new settlers would be making a start on their new homes in the wilderness before the end of August, 1821.

Lot Selection and the Construction of their New Homes

To view the lots, 2 or 3 would set out with a guide, to whom they had to pay 5 or 6 shillings a day for his services; with many of these excursions taking 3 days. Each immigrant would get to view at least 2 lots before making his choice, and assuming 3 of them had gone together, this would mean that all of them would have to inspect 600 acres – not an easy task on foot! As well they had to endure the hot weather of the days, and the cold and damp nights with the ever-present mosquitoes feeding on them. Due to their bites, it seemed that the men were "covered all over with the small pox, and attended with an equal itch."

Although it is not known when exactly (or recorded as far as I can tell anywhere), that John Gilmour Senior and his 3 sons set out to select their lots, but it would have been as soon after their arrival at New Lanark as was possible – probably within the first 2 weeks after their arrival on August 4th. The lots that they ultimately selected were all in Ramsay Township, and just a mile or so west of the town of Almonte. These lots were all fairly close together, (in fact John Sr's lot and his son James' lot abutted each other) which enabled them to help one another for the next very crucial task of building cabins, and getting ready for their first Winter in Canada. Again, it is not certain exactly who built their initial log cabins, but Peter Andersen suggested to me many years ago, that there were French Canadians available to either build, or assist, as they had the skills with the saw and axe, that most probably the former weavers and military men would not have had.

- The allocation of 100 acre lots was as follows:

- John Sr. – settled with his wife (and a boy under 12 [?], per LSS p. 123) on West Lot 13, Concession 7, Ramsay Township. However, according to the data from "Early Settlers of Bathurst" (fiche), John [senior] was with his wife, and a daughter over 12. This could possibly be Mary, born July 8, 1802.

- Allan – East Lot 15, Conc. 8, Ramsay Twp., with his wife and 3 children: girl (c. 1815), boy (c. 1817), and William (1821).

- Hugh – East Lot 14, Conc. 8, Ramsay, with his wife and 2 daughters, girl (c. 1817), girl (c. 1820). Janet was born here in 1821. Per LDS film data received from Bev Gilmour, these 2 unidentified daughters were – Anne was born 27 Feb. 1817, bap. 16 Mar 1817; Mary was born 8 Dec. 1819, bap. 20 Dec. 1819. NOTE: Per Twp. of Ramsay Land Record held by Archives Lanark (and a copy I have of it) Hugh received his Letters Patent from the Crown on June 26, 1837; but then sold the lot per Instrument #79 (a B&S = Bargain & Sale) on Nov. 16, 1840, with its registration on May 14, 1842 to a James Metcalf.

- James – East Lot 13, Conc. 7, Ramsay Twp., single on arrival, but per ship's list of "David" (per Granny's Genealogical Garden website), James is shown travelling with a female age 18. [Can she be his sister Mary, born July 8, 1802?]

See Appendix D for a Map of Ramsay Township, Lanark County, and the location of these 100-acre lots marked on it.

The size of these initial cabins was relatively small. John McFarlane indicated that his was built with logs, and was only 19 feet by 21 feet, but he did have a stone "vent" [or chimney] built in his. Many of the cabins would only have a "smoke hole" in the roof to start, so one can understand how difficult it would have been to keep the heat inside in the dead of Winter! The roof was covered with basswood logs split in half, and then hollowed out. [This would be accomplished by placing one log with the hollow down, and the next log with its hollow up, and "cupped together", to provide a waterproof roofing system.] The spaces between the logs of the walls would have been chinked – possibly with a mixture of mud and moss.

Victor Gilmour in front of James Gilmour's Original Log House – taken in 1997.

The British Government did provide a number of tools and materials to these new settlers, from their depot at New Lanark. See Appendix B for a list of some of these items. I understand that money was provided by the government to get the settlers through their first Winter, and until their own crops could be planted the next Spring – i.e. the Spring of 1822. According to a Mr. James More, of Ramsay Twp. (who came with his parents at age 9, in Carol Bennett's book), the sum was £8 – but £2 was to be withheld to cover over-land transportation costs for the settlers and their luggage to their lots. The remaining £6 was a "claim upon the land", meaning that the settler had to pay it back at some later date before he was to get his deed, or "Letters Patent" to his lot. However, again per James More, this claim of £8 was still unpaid up to 1841, and finally a Commissioner was appointed by the government to look into this situation, and he recommended in favour of the settlers, and thus the government assumed their debts, and finally issued deeds to their land.

Per the narrative of John McDonald, the crops grown would most probably be potatoes, Indian corn or maize, wheat, and barley. But, as he wrote "because there are 5 or 6 months annually, of severe frost and snow", life was difficult, especially insofar as growing their crops. As well, they were far from a market in which to sell any excess produce, the nearest being Kingston, or Brockville, both of which were about 60 miles away.

The second disadvantage faced, was the scarcity of draught animals – like horse and oxen, not to mention their cost. The third great inconvenience is the scarcity of grist mills and the distances that their grain must be sent to be ground in them. The nearest one was at Perth, some 14 miles from New Lanark.

However, there were things to be obtained from the nature around them: sap from maple trees could be boiled to produce sugar; herbs could be gathered as substitutes for tea; and wild fruit such as raspberries, strawberries, plums, gooseberries, and black currants could be picked. Although McDonald said there were no apple trees in the forest, there must have been some close by. And, of course, deer could be shot, fish could be caught in the rivers, and fowl such as wild geese and ducks, and wild pigeons that could be easily shot from the sky.

Not an Empty Land

Of course, though little has been written on the subject in Lanark County (as far as I know), we should not forget that the settlers were coming into land that had been occupied for thousands of years already by the indigenous peoples, or, as we now refer to them, the "First Nations" peoples. The British Government had made an attempt to legitimize the take-over of their lands, by the signing of dubious treaties. The treaty covering not only Lanark County, but a much larger area was Number 27, and 27 1/4, and it was initially signed in 1820 . It agreed to pay each individual the sum of £2, 10 shillings annually, but as you can see from the amount, many thousands of acres were ceded for mere pennies!

See Appendix C for more information on Treaty 27, which encompassed the land given to the new settlers.

We do, however, know of at least one inter-marriage of one of the original inhabitants, with one of the new British settlers, and that was the marriage of Joe Baye with a Miss Eleanor Slack. Besides Joe Baye, who had a small book written about his life, by Hal Kirkland , of Almonte, (i.e. "Joe Baye, a Genuine Canadian: and Other Stories", published by the North Lanark Historical Society in 1971), we also know of the Whiteduck family (Joe and Peter) through the wonderful blogs of Linda Seccaspina. Linda also mentions another indigenous inhabitant of the area, a Big Joe Mitchell. Here is the URL link to one such of Linda's blogs, covering some of Joe Baye's story: Eldon Ireton Talks About Joe Baye.

Per Howard Morton Brown, the natives of the Ramsay Twp. and Lanark Twp. areas were Mississaugas, a sub-tribe of the large nation of Ojibways. As the new settlers moved in, many of these inhabitants retreated northward, and westward, with some eventually ending up on Reserves in the Kawartha Lakes area.

Therefore, although not a lot has been written about the original peoples of Lanark County, we are fortunate indeed to have these 3 sources of named and admired men, who lived alongside our early European settlers.

Appendix A: Additional Information on the Construction and Ultimate Fate of the ship "David of London"

Note: Per page 28 of Marilyn Snedden's book titled "The Robertsons of Ramsay", published April 2006, and per the Lloyd's of London Registry Insurers, the "David of London" was built in 1812 in Pictou, Nova Scotia, a ship of 380 tons, full-rigged (i.e. with 3 masts), square sails, square stern, and made of black birch and pine, with copper sheathing below the waterline. She was 104' 9" in length, and 24' 4" in width, with a single deck. Fully loaded her draught was 16'. She was owned by James George, and skippered by a John Gemmill. A total of 364 Scottish settlers sailed from Greenock on May 19, 1821. In 1822 she was lost at sea between Londonderry, Ireland and Quebec, so it was a matter of luck that the emigrants had made it to Upper Canada the year before. On page 30 there is the photo of a model of a ship similar to that of the David of London.

Note: Per Karen Foote-Robinson, Oct. 16, 2014, "I just had a little look into the Ship "David" – this is a great resource if you are ever researching ships" – [Lloyd's Registry].

"It seems The David was captained by Gammill {sic} from only 1820. The ship was built in 1813 and for all those years till Gammill / Gemmill, was captained a man by the name of Peacock. It was an A1 ship when built but had gone down to a Second Class by the time our ancestors crossed in it (E1 – still of first quality though). It was 390 tonnage with some repairs, Single Deck with Beams, made of Black Birch & Pine."

I looked at the same site and page, and found the string of coded description as follows:

6 S sC J. Gammill 390 Pictou [N.S.] 9 J.J. George 16 Lo.St.Jhn's E 1 F ! X2 BB&P Srpxx sdb Iron Cable

Means: 6 – line item number; S – "Ship"; sC – sheathed with copper; J. Gammill as

master/captain; 390 – tons; Pictou – place built; 9 – years since ship built [circa 1812];

J.J. George – owner; 16 – ??; Lo. – London; St.Jhn's – probably St. John, N.B., the surveying port;

E – second class ship; 1 – materials of the ship of First Quality; F ! – ??; x2 – years since last

surveyed, i.e. no review of the ship since 1819; BB&P – made of black birch & pine; Srpxx –

some repairs; sdb – single deck with beams; Iron Cable – ?? [possibly it means an iron anchor chain cable].

Note: Per GOOGLE Books on Nov. 19, 2010, I found a book called "WOOD: Volume 24", and in it there is a reference to another voyage of the "David of London", this time on August 4, 1821, sailing from Greenock to Quebec, and on board her were James Gillies and his wife Helen Stark. "The ship, under the command of Capt. Gemmill, carried chiefly country people from the counties of Lanark, Dum . . . ." [end of page].

Note: Per an interesting coincidence, another Capt. Gemmill (this time an American, from Pennsylvania – per my Gemmill File), this time Capt. Hugh Gemmill, buried in Christiana Presbyterian Church (founded 1738) graveyard, died on Nov. 29, 1822 at age 55 years, 11 months, 4 days [bc. 1766]. This would be the same year that the "David of London" sank! Also, Hugh's wife Jane died August 17, 1826, age 55 years and 9 months.

NOTE: Per my venture into British Newspaper Archives (on-line) in Oct. 2014, I found reports of a huge storm that caused many ship wrecks, including that of the "David", reported in the Morning Post, Monday 18 November, 1822 – the "David" with Gemmill [as captain or master] from St. John's, New Brunswick [it should be either St. John's Newfoundland or St. John, New Brunswick] to Glasgow, abandoned at sea on the 9th. ult. [i.e. the 9th. of October, as "ult." refers to in or of the month preceding; "inst." means current month]. It apparently floated into Roundstone Bay (Roundstone is in County Galway, on the west coast of Ireland, NW of the town of Galway, and SW of the town of Westport, which is also mentioned in the article), with its load of timber intact, but its cabin ransacked of its furniture, etc. by local "pirates" [my terminology], or more probably those just taking advantage of salvage.

Note: Per Karen's reply on Oct. 18, 2014:

Hi Ken –

There is a column in the information which shows (in 1821) that the ship is 9 years old; but

rather than going straight back to 1812/13 I went back to 1820, could see Gemmill was still

captain, then back to 1819, and as I had well established the ship's information, though it was

under the name of Captain Peacock, the information on the ship identified it as the same

"David". In one of those columns, it had under it x3 which indicates it was built/registered in

1813 (i.e. the year of the same decade the x indicating the decade 1810). Then I could go

confidently go back to 1813 and find the first instance of the ship David which was still under

Peacock. Also, the ship changed owners after Peacock as well.

I had forgotten about the ship being lost the year later; do you have a death year for Gemmill or does he just fade away after the ship was wrecked?

Wikipedia (as this is another great resource when researching ships) and its Wrecked Ships data; have just put in the entries (listed twice) with the reference information: List of shipwrecks in 1822. 9 October - David (United Kingdom): The ship was wrecked in the Atlantic Ocean with the loss of seven of her seventeen crew. Survivors were rescued by Woodbridge (United Kingdom). She was on a voyage from St. John, New Brunswick, British North America to Glasgow, Renfrewshire. ["Ship News" The Times (London). Thursday, 10 October 1822. (11692), col E, p. 3.] Note: I looked at Lloyd's list and found the following for 1822 on the Ship "Woodbridge": Captain Smith, 480 tons, Ship E-1, Built in Calcutta, India, approx. 1809, Sheathed with Copper & Iron Bolts, Owner: Mangles, London was the surveying port. Per image sent to me by Karen, from the Caledonian Mercury newspaper, Monday 21 October, 1822, the account reads as follows: "The David, Gemmell, from St. John's {sic}, N.B., for Clyde, was fullen in [filled with] with water on the 9th. instant, [Oct. 9th.] water logged. Seven of the crew had been washed overboard, and the master and nine men were with difficulty taken off by the Woodbridge, arrived at Kinsale." [Kinsale is on the south coast of Ireland, just south of Cork and Cobh.] David (United Kingdom): The ship was wrecked at sea before 10 November and was abandoned by her crew. ["GALES ALONG THE COAST" The Times (London). Tuesday, 19 November 1822. (11720), col E, p.2.]

As this mentions the ship that rescued them, I looked again in the papers.

– Caledonian Mercury (Edinburgh, Scotland), Monday, October 21, 1822 – attached.

– The Morning Post (London, England), Friday, October 18, 1822 (strangely this one was a huge

file so won't send but says mostly the same).

So, if Gemmill lost several men at sea it would have been quite a burden on him wouldn't it, and may support your theory of suicide.

I was surprised when I looked in Lloyds initially and found it was built in Canada, so am unsure why it was registered in London, hadn't come across that before though I've only researched a few ships. I'm just wondering if it was formally known as David of London, or if that is just something that came about with the migration records later, as it did a run from London to St John's etc. Or as Canada was still part of the British Empire it was normal to register it in London . . .? after all, it was British ship.

My Reply to Karen (also Oct. 18, 2014):

Hi Karen,

Thanks – now I see you did a little detective work to ferret out the data on Peacock.

Re Death Date for Capt. Gemmill: It was in original note (see attached, but near the bottom), so

here it is again – Capt. Hugh Gemmill, buried in Christiana Presbyterian Church (founded 1738)

graveyard, died on Nov. 29, 1822 at age 55 years, 11 months, 4 days [bc. Dec. 1766]. This would

be just 51 days after the "David" was abandoned at sea, so plenty of time for him to return to

the USA, and die (by whatever cause?) It would be interesting to see if you or I (or anyone else

interested in the Gemmill families), could find out more info. on this Hugh Gemmill and his wife

Jane, as to whence they came (possibly from Ayrshire, SCT?) before they settled in

Pennsylvania, USA.

Although the "David" was built in Pictou, Nova Scotia, she may have become known as the

"David of London", since that was the port where she was "surveyed" – per the ships' codes in

the Lloyd's document. As I read the entry, the "x2" code (right before the "BB&P" {black birch

and pine}) means that the ship was not surveyed (I'm guessing that term means checked-out,

by Lloyd's) since 2 years prior at London, which would be circa 1819. I believe today, many

ships have Liberian Registration, even though they come from all over the world, because of

insurance rates, or some such thing. Maybe Lloyd's gave a preferential rate if the ships in the

1820's were registered in London, and could be "surveyed" there by their professional

agents/assessors?

Many thanks for the additional data you found on Wikipedia too!

Ken

Additional Information on Cargo and Passenger Ships – per Helen I. Cowan

Per Ms. Cowan (page 11, "British Immigration Before Confederation") cargo and passenger ships could well be one and the same! The reason for this is that it depended upon which direction the ships were sailing!

"Until 1842, the timber shipping owners provided three-quarters of the tonnage in the British North American trade. Once the timber products from the colonies were unloaded in the British port, the windowless timber hulk was cheaply lined on all sides and down the centre with double tiers of six-foot square bunks and filled with hopeful emigrants. Emigrants travelling in these bunks in the ship's hold were said to be supporting the shipping merchants at the rate of £650,000 a year; for such accommodations and locating himself in the colony an emigrant needed at least £50 in cash. To travel in the ship's cabin with his family and buy colonial land on arrival would cost a man possibly £500."

Hence, if the ship were sailing from Canada to Britain, it would be a cargo ship filled with timber (much of it was for masts and spars for the British Navy). If the ship were sailing from Britain to Canada, the necessary "ballast" would consist of paying passengers, and what worldly goods they could bring with them.

Appendix B: Supplies and Tools Provided to the Settlers

- Bedding for Every 4 Settlers: 4 Palliasses, 4 blankets. (NB – A palliasse was a cotton bag, which, when filled with spruce or bracken, and later on straw, served as a mattress).

- One Blanket for each married woman and each child, and one palliasse to a family with more than one child.

- Building items for Every 4 Settlers: 72 small panes of glass (7.5" x 8.5"), 6 pounds of putty, 4,000 feet of pine boards, 48 lbs, of assorted nails.

- Seed for Every 100 Settlers: 150 bushels of potatoes, 200 bushels of oats, 200 bushels of fall wheat, 200 bushels of spring wheat, 25 bushels of Indian corn (i.e. maize), 7 bushels of beans, 13 bushels of grass seed.

- Implements between Every 15 Settlers: 1 grindstone, 1 pit saw, 1 cross-cut saw. One set of blacksmith's tools to each Township.

- Implements for Every 4 Settlers: 4 felling axes, 1 broad axe, 4 hand saws, 4 locks and keys, 8 door hinges, 4 iron wedges, 4 pitch forks, 4 iron pots, 4 frying pans, 8 gimlets [probably auger gimlets, to drill small holes by hand], 8 assorted files, 4 chisels, 4 augurs, 4 scythes, 4 sickles, 4 spades and shovels, 4 pick axes, 4 broad hoes, 4 narrow hoes, 4 carpenter's hammers, 4 adzes, 4 drawing knives, 4 brush hooks, 36 harrow teeth, 4 wood planes.

Appendix C: Treaty Number 27

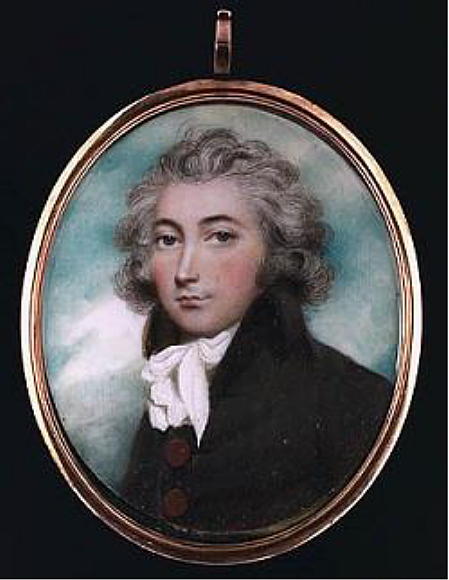

A miniature of Colonel William Claus. He was the Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs at the time of the Purchase.

(Library and Archives Canada).

Treaty 27 and 27-1/4, or the Rideau Purchase, was entered into on May 31, 1819, and confirmed in 1822 by representatives of the Crown and certain Anishinaabe peoples. Note that the Treaty's confirmation was the year AFTER the settlers were on "their" new farms!

The Rideau Canal, a vital waterway in Upper Canada, was built through this territory after the Treaty was signed.

This Treaty covered a huge area, as follows: ". . . all that parcel of tract of land situate, lying and being in the Midland and Johnstown Districts of the Province aforesaid, containing by admeasurement two million seven hundred and forty-eight thousand acres, be the same more or less, which said parcel or tract of land is butted and bounded, may be otherwise known as follows, that is to say: Commencing at the north-west angle of the Township of Rawdon; then along the division line between produced north sixteen degrees west from the north-east angle of the Township of Bedford; then north sixteen degrees west to the Ottawa or Grand River; then down the said river to the north-west angle of the Township of Nepean; then south sixteen degrees east fifteen miles, more or less, to the north-east angle of the Township of Marlborough; then south fifty-four degrees west to the north-west angle of the Township of Crosby; then south seventy-four degrees west sixty-one miles, more or less, to the place of beginning."

Note that this Treaty covered an area of 2,748,000 acres! The remuneration to be paid to the natives for this huge area of land, was described as follows: ". . . the said William Claus, and his successors in the said office, shall and will well and truly pay, or cause to be paid, unto each man, woman and child of the said Missisagua {sic} Nation of Indians who at the time of entering into the said agreement inhabited and claimed the said tract of land, and to their descendants and posterity forever, an annuity of two pounds and ten shillings of lawful money of Upper Canada, in goods and merchandise at the Montreal price, provided always that the number of persons entitled to receive the same shall in no case exceed two hundred and fifty-seven persons, that being the number of persons claiming and inhabiting the said tract at the time of concluding the provisional agreement hereinbefore mentioned."

Therefore, in summary, for the area of 2,748,000 acres, each man, woman, and child of the Missisagua {sic} Nation were to be paid in goods and merchandise, the equivalent value of £2, 10 shillings as an annuity – provided that their numbers NOT exceed 257 persons!

Therefore, some simple math shows that the total commitment by the Crown (per annum) was the sum of £642 pounds, 10 shillings!

Appendix D: Map of Ramsay Township, Lanark County, Showing Location of the Four Gilmour Lots

- "John G." – designates John Gilmour Senior, who was on West Lot 13, Conc. 7. He is the father of James, Allan, and Hugh. Crown Patent to lot issued on June 26, 1837.

- "J.G." – designates his son James who was on the adjacent lot, East Lot 13, Conc. 7. Crown Patent to lot issued on June 26, 1837.

- "A.G." – designates his son Allan Gilmour, who was on East Lot 15, Conc. 8 – The Auld Kirk graveyard is kitty-corner to Allan's Lot. Crown Patent to lot issued on Sept, 20, 1837.

- "H.G." – designates his son Hugh, who was on East Lot 14, Conc. 8. Crown Patent to lot issued on June 26, 1837.

Location of the farms of John Gilmour Sr., and sons James, Allan and Hugh.

Appendix E: Financial Data Regarding the Payment of the "David", and Relative Value in Today's Currency

Per the Edinburgh Courant newspaper, May 26, 1821:

The money lodged for the outfit of the vessel, for provisions, and freight of the societies [i.e. the Emigration Societies], was £1,198.11s.8d, and after paying all of the charges, the emigrants received, to be divided amongst them . . . £93.11s.8d.

The passengers were chiefly country people from the counties of Lanark, Dumbarton, Stirling, Clackmannan, and Linlithgow.

Per an internet website: The value of £100 in 1820 would be £9,914.11 today. As well, in 1830, £1 would be the equivalent of £108.58 in 2017. So, taking both of these figures into account, it would seem that one pound sterling in 1821 would now be worth approximately £100. At the current exchange rate of £1= $1.71 Canadian, we would have £1 in 1821 now being worth $171.00!

Appendix F: Data on John Gemmill Senior from Fran Cooper

Per copies of documents – a letter, Glasgow Trongate record data, and a certified document from John Gemmill's son, Andrew, we have the following data:

Per a letter that John Gemmill wrote from Lanark, Upper Canada, to his wife Ann (nee Weir) Gemmill and his family still in Glasgow, Scotland, dated March 2, 1822 (and received by her son Andrew there on November 23, 1822 – almost 9 months later!) we note that John McFarlane, (the author of the wonderful journal of the ship "David" sea journey from Greenock to Quebec City) had settled close to him. "John McFarlane and family are well and are settled about two miles from me." Note as well, that this letter of advice would never have been received by his wife Ann, as she and 7 of her children had already left Scotland in June of 1822!

Per Glasgow Trongate data, we can see that John Gemmill, age 45, had paid his emigration society in 2 installments for his voyage: the first amount was £2.10.0, and the second £1.15.0, for a total of £4.5.0.

Per a document, certified by Andrew Gemmill, John's son who had stayed behind in Scotland when the rest of his family had emigrated (due to advice that his lame leg would be a significant hindrance to his success as a farmer there), we know that John Gemmill Senior had emigrated from Glasgow on Wednesday, May 16, 1821. [NOTE: It seems to have been a common practice for those planning a departure from the port of Greenock, to arrive there a few days early, and possibly take rooms in a hotel or lodging house, to ensure not only that they were ready ahead of time, but also to ensure that any baggage would also arrive in time for loading onto the ship. Thus, his son Andrew is telling us that his father, John, actually left Glasgow 3 days before the sailing of his ship "David".] Andrew goes on to say that his father John settled on Lot 13, 8th. Concession of Lanark [Township], Upper Canada.

John senior's family (comprised of his wife, Ann Weir, and the following children: Janet, Ann, Mary, John Jr., Marion, Elizabeth, and David) left Glasgow on Wednesday, June 12, 1822. Their daughter Jean remained behind in Scotland, and married John Arnott on February 24, 1826 in Glasgow, and later came to Canada with her husband John.

Note that Andrew, despite his physical handicap, became a successful and prominent lawyer in Glasgow, married, and had a large family. He also came to Canada alone to visit his family in 1842, and while there, drew up a large circular family genealogical chart of the extended family that came to greet him at his father's home, on August 23rd, 1842.

Appendix G: Additional Data on Scottish Emigration from Robert Lamond's Book – Published in Glasgow in 1821

Vaccination

Per page 41: At Glasgow, March 16, 1821, meeting held in the Counting-House of William McGavin, Esq., Convener, of The Committee of Emigration from the West of Scotland, to His Majesty's Settlements in Upper Canada, their fourth Resolution – "That the parents of all the children who belong to different families of Emigrants, who have not been inoculated for the small-pox, must cause the same to be immediately done, as the children will be inspected by the surgeons, before they can be admitted on board. Such parents who may have any prejudice against vaccination, must remove their objections, or their children cannot proceed."

So, it is interesting to find that, 200 years ago, the question of vaccination was first and foremost in the minds of the officials, and parents of those wishing to emigrate to Canada, and that the question of mandatory vaccination, for certain purposes, is not a new one!

Other Ships and Emigration Societies that Sailed in the Same Time-Frame in 1821 – p. 63

| Ship | Tons | Soc. | Pass. | Money | Sailed | Arrival | Births | Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| George Canning | 485 | 11 | 490 | £1533.7.10 | Apr 14 | June 1 | 3 | 5 |

| Buckinghamshire | 600 | 7 | 607 | £1923.13.11 | Apr 29 | Jun 15 | 6 | 1 |

| Commerce | 418 | 9 | 422 | £1316.12.0 | May 11 | Jun 20 | 0 | 3 |

| David | 380 | 10 | 364 | £1198.11.8 | May 19 | Jun 25 | 4 | 3 |

| Total | 1883 | 37 | 1883 | £5972.5.5 | 13 | 12 |

- Ship – name of ship – e.g. Earl of Buckinghamshire

- Tons – Tonnage rounded to nearest whole ton

- Soc. – Number of Emigration Societies in each ship

- Pass. – Number of passengers in each ship

- Money – Money (£.s.d) lodged for provisions and transport, some refunded at voyage end

- Sailed – Date Sailed

- Arrival – Date the ship arrived in Quebec City

- Births – Births during the voyage

- Deaths – Deaths during the voyage

Several Other Letters from Newly Arrived Settlers

Note that Robert Lamond's book contains several letters from other settlers with valuable first-hand information on their personal experiences.

One of these was a John McLachlan, who is mentioned twice: firstly, on page 15, in a letter written to Mr. Lamond, written in Greenock on July 8th, 1820, in thanks for all that has been provided, and signed jointly by John M'Lachlan {sic} and Thomas Whitelaw; and secondly, on page 49, in a letter written to Kirkman Finlay, Esq. M.P., written from New Lanark in Upper Canada, and dated December 11th, 1820, containing advice as to the timing of future migrations. Note as well that William Marshall, Superintendent of the New Lanark Settlement, takes advantage of M'Lachlan's letter, and appends his own letter to it, providing additional information on the nature of the new settlement, the importance of cash to the new settlers, and again emphasizing the importance of sending out settlers earlier in the season, and to arrive not later than July.

Appendix H: Their Route from Brockville to Perth – per Research Done by Ken. W. Watson

Source: Perth and District Historical Society. Thanks to Frances Rathwell and Marilyn Snedden for identifying this source to me. The title of this extensive article (which can be found under the "History" tab), is "The 1816 Routes to Perth – A Narrative of Discovery", by Ken. W. Watson.

Although Ken Watson's document specifically addresses the route taken by earlier settlers from Brockville to Perth in April of 1816, I assume that logically those travelling 5 years later (in 1821) would take virtually the same route. As well, since neither the Journal of John McFarlane, nor the book by John McDonald, mentions any water portion by scow of 22 km. over the Big Rideau Lake, I am assuming that our settlers used the "Fall 1816 Route", rather than the "Spring 1816 Route".

Thus, their journey would have gone through the Townships of Elizabethtown, Kitley, South Elmsley, and finally North Elmsley. More specifically, their route would have been: from Brockville via County Road 29 (formerly Highway 29) to Forthton, through Frankville to Toledo (which did not exist at that time), and then following County Road 1 to Lombardy, and then crossing the Rideau Lake at Oliver's Ferry (now known as "Rideau Ferry"), and past the north end of Otty Lake, to Perth.

I highly recommend reading all of Ken Watson's wonderful article on the above website, complete with many old maps, sketches, prints, and present-day photographs of the places and terrain on this route.

Appendix I: Additional Information on the Steamship "Lady Sherbrooke"

Per an article written by Alan Hustak, and published in the "Montreal Gazette" newspaper on May 29, 1989, we have the following data.

The "Lady Sherbrooke" was the fourth of five steamships in the fleet, built by John Molson, who was a brewer in Montreal. She was launched in 1817, and involved in an "accident" on May 2, 1823. There is speculation that she intentionally rammed the stern of the rival steamship, "Salaberry", (causing some damage, and the loss of a small boat) which was owned by Molson's rival, James Torrance.

The other 4 steamships in Molson's fleet were "L'Accomodation" (1809), "Swiftsure" (1812), "Malsham" (1814), and the "New Swiftsure" (1818).

The "Lady Sherbrooke" was scrapped in 1828, and her hull was left near Ile Ste. Marguerite, near Boucherville, Quebec. Her hull was found in 1963, correctly identified in 1983, and excavated by Jean Bélisle, a marine historian, and by André Lépine, an archeologist.

In 1989, an exhibition of this steamship (model, and artifacts recovered), was held at the David M. Stewart Museum in the Old Fort, on Ile Ste. Helene, Quebec.

If one is interested in reading much more detail on the discovery of the "Lady Sherbrooke", then go to this website: www.waymarking.com. Note that the first half of the page is in French, then the same information is repeated in English.

Appendix J: Source Materials

My sources include the following books, and pamphlets:

- "Narrative of a Voyage to Quebec, and the Journey from thence to New Lanark in Upper Canada" – by John McDonald, a Lanark Society Settler of 1821, originally published in 1823. The book was re-published by Global Heritage Press in 2016, with ISBN Number 978-1-77240-044 - NOTE: Excerpts from this book are used with the kind permission of Rick Roberts, of GlobalGenealogy.com Inc., Carleton Place, ON, Canada, K7C 1J2.

- "The John McFarlane Journal" [1821, per the Toronto Reference Library,] transcribed by Charlie Dobie. (The link connects to the transcription on this website).

- "The Lanark Society Settlers" – by Carol Bennett McQuaig – published by Juniper Books Ltd. in 1991.

- "A Dictionary of Scottish Emigrants to Canada Before Confederation Volume 2", by Donald Whyte F.H.G., F.S.G., etc.

- "A Narrative of the Rise and Progress of Emigration from the Counties of Lanark and Renfrew to the New Settlements in Upper Canada, etc. etc." – By Robert Lamond, Secretary and Agent, originally published in Glasgow, Scotland in 1821. Printer: James Hedderwick for Chalmers & Collins, 68 Wilson Street. The current facsimile edition was produced by Canadian Heritage Publications, and printed by M.O.M Printing in Ottawa in 1978.

- Newspaper Account of David's Sailing from Greenock – Source: britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk Note that one must have a paid subscription to The British Newspaper Archive to be able to view the item from this link. Actual Newspaper Source: Westmorland Gazette – Saturday 02 June 1821. Article had been copied from the Edinburgh Courant newspaper on May 26, 1821.

- "British Immigration Before Confederation" – Historical Booklet No. 22, by Helen I. Cowan, a publication of The Canadian Historical Association Booklets, Ottawa, 1968.

Conclusion

In closing, I would like to say that I am proud of ALL of my ancestors, (whatever their surnames may be), and of their sacrifices and determination that have made my life possible. I hope that most of you have enjoyed this tale of migration and settlement, and if any reader of this protracted story has any comments, additions, clarifications, or corrections, I would be most happy and grateful to receive them. You may do so by contacting me via e-mail: (ken.godfrey1@gmail.com), or in the old manner (if you do not have e-mail, or my electronic address has changed in the future), by writing to me – Ken Godfrey, 94 Wishing Well Drive, Scarborough, Ontario, Canada, M1T 1J4.

Thank you.

Ken Godfrey – December 15, 2021