Adapting to Ryland while Keeping the Best From Ukraine.

By John Guty.

Guty, Stephan & Katherine

Children: John, Nadia (Nida), Vola

Hearst Relations: Giecko

My parents were of Ukrainian descent and were born and grew up in Kulno, a border village, controlled by the Austro-Hungarian Empire until 1918 when the region was transferred to Poland. Since we always called my father Tata and mother Mama, it will be used here when referring to them.

Births: I was born in the Teltaka railroad station in 1932. Teltaka was a whistle stop on the CNR railway between Hearst and Nakina.

John & Katherine Guty in Teltaka, about 1933.

The rail line no longer exists. My father was a section man on the railroad. As there was no doctor, a midwife, Mrs. Plawliuk, attended my birth.

Eventually, I had a sister, Nida, born in Nagogami in 1934, and a brother, Vola, born in Ryland in 1936. Of the three places, Ryland was the biggest. It had farms.

Father: Stephan Guty was born in Kulno, Poland, in 1896 and came to Canada with a friend in 1926. He was thirty-one. They worked in Manitoba clearing land. When the job was done, they hitched rides on freight trains, heading east in search of work. Eventually they came across a CNR section crew east of Nakina, where the foreman was looking for workers. Father hired on and continued working on the Cochrane division (Fitzpatrick, Quebec, to Nakina, Ontario), until 1962. He worked primarily on the Pagwa subdivision, which ran west from Hearst to Nakina, and later on the Kapuskasing subdivision, which ran east from Hearst to Cochrane. There were stations every ten kilometres from which the section crews worked. A section crew consisted of a working foreman and two labourers, plus one or two extras in the summer when the tracks had to be levelled after heaving and settling in the spring. Also, ties that were rotting were replaced. Track maintenance was very hard work and attracted many immigrants from Eastern Europe used to working from sunrise to sundown. Here they had a job where they only worked eight hours a day, six days per week.

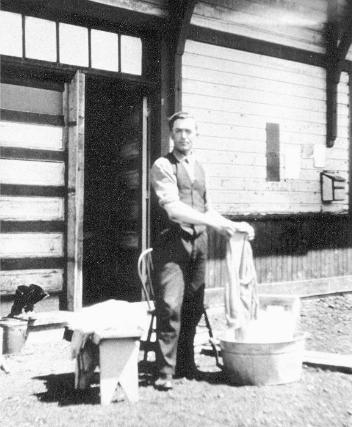

Stephan Guty, about 1930.

Mother: Katherine Cwiak was born in Kulno in 1900. She was brought up by her mother, as her father was killed by a Russian border guard. Mama never forgave them. She called them muskali, a derogatory term for a Russian with authority. Mama went to work when she was ten. Later, her uncle trained her to weave cloth. In 1931, after Tata had been in Canada five years and had become a British subject, he returned to Kulno to marry her. I was conceived in Poland, but was born in Canada.

Canada: Both parents loved Canada, though Mama hated the cold, swamps and stunted black spruce of Northern Ontario. The climate back home was temperate with clean pine forests. But language, religion, education and the printed media were suppressed. To them, Canada, with its freedoms, was a country of opportunity. Within ten years of Mamaís arrival, they had bought a farm and were planning a house. This was unheard of in Poland. By the late 1930s, Tata had bought a radio and, in 1941, a 1936 Chevrolet – rare even for Canadians of the period.

Culture: At home we spoke Ukrainian. Mama always stressed that we were Ukrainian, even though some ignorant people called us Polaks or Hunkies. On Saturdays, she taught us how to read and write. I even wrote letters to Didus Naoom, a phantom grandfather at the Ukrainian Voice newspaper, a weekly newspaper with Orthodox leanings.

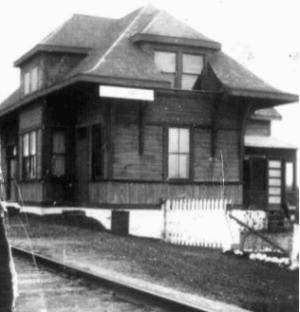

Nida, Katherine, & John Guty at the Ryland train station, about 1936.

School: I began school in 1938 at age six. By choice I went alone. The school, S.S. No. 1 Hanlan, Ryland, was a two-kilometre walk. It was one room with Grades 1 to 8 and from fifteen to twenty-five students. The schoolyard included a United church (Sunday services summers only), where we held Christmas concerts. There was also a ball diamond and an unfinished building where we played at recess, which we called the hall. It was built of timbers with a shingled roof, but had neither windows nor floor, only wooden cross members, which we used to run over. Behind the school was a woodshed with two toilets attached. Eatonís or Simpsonís catalogues served for toilet paper. Drinking water was brought to the school in a metal bucket by one of the Achilles kids. We all used the same metal dipper. The school day started with reciting the Lordís Prayer and singing "God Save the King." Canada did not have an official national anthem, so "God Save the King" was accepted, because it was part of the British Commonwealth. Sometimes we sang "The Maple Leaf Forever," "O Canada," or "Rule Britannia." My Grade 1 teacher was Miss Clapp. Subsequent teachers were Mr. Britain Grade 2, Miss Laura Davidson Grade 3, Miss Mary Poberezec Grade 4, Miss Nettie Kowalchuk Grades 5 and 6, Mr. Shaver Grade 7 and Miss Terefenko Grade 8.

The school was cleaned daily by one of the students. Cleaning consisted of sweeping the floor and washing the blackboards. The pay was $5 a month in the summer and $8 in the winter; more in the winter because you had to be there earlier to light the fire. You also had to keep the fire going all day.

High School: High school was in Hearst, ten kilometres away, which meant I had to board in town. My first year I boarded at Derkusesí, a Ukrainian family. I hated living there. The meals were not like Motherís, though the accommodation was okay. The following summer, Tata bid on a job in Hearst and got it. For accommodation he relocated our chicken house from Ryland to McManusville. The chicken house became our home in town. The next year, Tata expanded it because Nida and Vola were starting high school. Mama was left on the farm and hated it. After three years alone, the farm was sold and she moved into town.

This was a very young high school, incorporated in 1942 in name only. I started in 1946. It had no Grade 13, which was required for university entrance. The classes were all in English, but there were two French classes, basic French for non-French students and special French for French students. There were two classrooms, one in the public school and one in the separate school; Grades 9 and 10 in one and Grades 11 and 12 in the other. The following year, because of increased enrollment in the Separate School, we had to leave. On the public school grounds, there was an abandoned one-room schoolhouse which was renovated and divided into two classrooms. Until the new high school was built, our facility was "second-rate" – some of the teachers, too. I could not understand why we had to take Latin, or memorize poems, or why French was taught by a Scotsman; I had a hard time understanding his English. Mrs. Bertha Fisher was the principal. She was a kindly old lady with blue hair. Other than the Scotsman, the other teachers were French from the Sudbury area. Generally, they were young and very good.

School Dances: Danielle de la Touche from France was the first girl that got me on the dance floor and showed me a few steps. Her father was posted to Hearst by the French government to oversee a forestry operation on five townships that were owned by France. Apparently, during the First World War, Canadian troops had devastated a French forest and, as compensation, Canada gave France this land west of Hearst. She was a slim, good-looking girl and always well-dressed. Why she picked me, I will never know. Maybe she felt sorry for an uncultured Canadian. Sometime during Grade 12, I became friendly with Margaret Nichols. We kept up this friendship for two years until I got a "Dear John" letter.

First Traffic Offence: Driving home from one Friday-night dance, the OPP pulled me over for having no tail-lights. We seldom drove at night and had paid no attention to this problem. The summons came by mail. I was to appear before Magistrate Tucker on Tuesday morning. Tata gave me the money, but there was a problem – I had an exam to write. Nervously, I approached the towering OPP officer with my dilemma. "Run along, sonny," he said, "and come back after you write your exam." I returned and paid my fine – my only court appearance, ever.

Youth Group: Sometime during high school, the United Church minister organized a non-denominational youth group. There would be dances in the church basement chaperoned by the minister. Several French kids attended until the Catholic priest put a stop to it.

Religion: Since Mama did not want us baptized Roman Catholic and was not familiar with any of the other religions, we were baptized in my auntís Russian Orthodox church, in Philadelphia. It was a long way to go, but since Tata worked on the railroad, we travelled gratis. She also drilled into us that we were Orthodox; not Catholic or Protestant, but Orthodox.

Ryland had two churches, a United church, which we attended in summer when the minister came, and a French Roman Catholic church. It wasnít until high school that I realized you did not have to be French to be Roman Catholic. Sunday was also the day people came to meet the 9:00 a.m. train to Nakina. The train was always met by Mr. Talbot, because he was the postmaster and most of the mail came on Sunday. After church, people gathered at Talbotís General Store, chatting until the mail was sorted. With no service in Ryland, we never went to church at Christmas or Easter. We celebrated Christmas in our own way. On Christmas Eve, after work, Tata would go out on snowshoes and come back with a tree, usually the top of a tall black spruce. He preferred balsam, but could never find one. Mama would decorate it. Christmas dinner was chicken with all the trimmings. Ukrainian Christmas was very different. We always had a traditional Sviatyj Vecher meal. Mama baked the babka earlier in the week and then prepared twelve traditional dishes for Christmas Eve. Also on Christmas Day, January 7, she kept us at home from school.

First Home a Station: The station was built to serve a future town, which never developed. It was an impressive wooden building consisting of a waiting room, baggage room and a residence for the train dispatcher. Because of under-use, we got to live in the baggage room – one room upstairs, one down. We lived there until 1942, when we moved into our own house.

Ryland Train Station.

Ryland: Inhabitants here were predominately French. Some of the non-French families were Molund, Knutson, Palmquist, all Swedish; Hendrickson, Finnish; Borg, Laplanders; Guty and Giecko, Ukrainian; Mitchell (three families), Turner, Steels, Achilles (two families), Marshall, Greeley (two families), Halgren, Newhouse, Dumont, all English. There also were several bachelors: Messers Anderson, Oslund, Helbert and Eric Johnson, were Swedish; Joe Poye, Croatian; Sam Myles, Henry OíRourke, English: Old Man Mike, Russian (I never did learn his name; everyone called him Old Man Mike). There also was a widow, Mrs. Nelson, and Mr. Anderson, who lived with her.

Tata, Mr. Giecko and Mr. Palmquist were the only ones with steady jobs and regular pay cheques. The others tried to live off the land, but wound up doing bit work – cutting pulp, working in sawmills, extras on the railway. With the war in 1939, most of the non-French left to join the army or work in cities. The French did not believe in the war effort and most never joined.

In 1939, my parents bought the Newhouse farm, opposite the railroad station. Mrs. Newhouse had died and her only son, John, was joining the army. Tata paid him $100. The farm had 120 acres, but most of it was untillable swamp. It had a small log house, which eventually became a stable for the cows. We now had property and could build a house and leave the station.

Guty house under construction, 1939

(Vola, Katherine, Nida, & John Guty)

Building the House and Barn: In 1940, Mr. Helbert built our chicken coop. A year later, Ed. Larson from Hearst, a super carpenter, designed and built our house. The basement was excavated by horses and a scoop. The forms for basement walls were made from tongue-and-groove lumber, which was later used for the walls of the house. A gasoline-driven cement mixer was used to mix the cement. It was the only piece of power equipment on site. With no electricity, all cutting was done manually. In 1942, we moved in. Our house and Molundsí were the nicest two in Ryland. Ours had eight rooms and provision for a bathroom. There was neither electricity nor running water, save for the hand pump in the kitchen. Our toilet was an outhouse near the chicken coop, but we had features other families did not – a bathtub for Saturday night baths (water heated on the kitchen stove and brought to the basement by Mama); an inside toilet in the basement with a honey pot, when it was too cold to go to the outhouse (Tata emptied it); furniture purchased from Eatonís.

Nida & John Guty (army cadet) 1946

Hearst: Hearst was the town. It had stores, a hospital and schools. Though we didnít realize it at the time, in the 1940s, it was only thirty years old and still evolving as a municipality. The streets were gravel, sidewalks were wood, water and sewage was only supplied along George Street. It was also a town where bush workers congregated when not cutting in the fall freeze-up and spring thaw. During this time, they lived in various rooming houses along Front Street, owned by the French and the Finns. Several bootlegged to their captive clientele. The archaic Ontario liquor laws spawned illegal drinking – bars opened at noon, closed from 6:30 until 8:00, so the men would go home for supper, then shut down at midnight. They were closed Sundays.

Career: The only working opportunities were in the bush, in local stores, or maybe the railroad. School ended at Grade 12, which left you a choice: find a job or further your education by taking Grade 13 in Kapuskasing. Another possibility was going to Ryerson Institute of Technology in Toronto. As I was the oldest, and with Nida and Vola coming along in two years, my parents couldnít afford to have three away at school at the same time. Tata solved the problem by suggesting I learn a trade. Through the CNR, he got me in as an apprentice in the motive power shops in Montreal. In 1955, I graduated as a diesel locomotive mechanic. After one year applying my trade in the Cochrane, I began a three-year course in mechanical technology at Ryerson.

Reflections: When I look back on what our parents accomplished, Iím amazed at how their lives revolved around us. We took it for granted, never appreciating their struggle. In the early 1940s, they bought a farm in Ryland, built a house on it, then bought a lot in McManusville, where they built another house. In 1955, they moved to Cochrane, and in 1962, after Tataís retirement, to Toronto. Each move was done for us: to Hearst so we could go to high school; to Cochrane to make it more convenient for us to come home; to Toronto to get Mama away from the cold and close to a Ukrainian Orthodox Church and an active Ukrainian community.

Can you provide corrections or comments?

Please report technical issues to: