March 6, 2024.

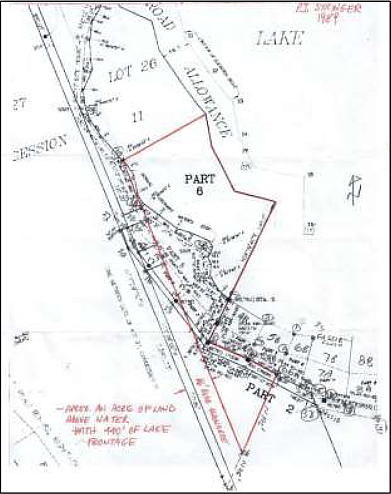

I had always coveted the little rocky outcrop just past the edge of our property on Sleepy Hollow Lane and often told the neighbour if he ever wanted to part with it, to let me know. He was reluctant to go through a severance process but, since this was a simple add-on to our property, we finally came to an agreement in 2007. He drew up a sketch of the land he was willing to part with, specifying that he wanted to retain a sixty-six-foot buffer along the boundary between lots 26 and 27, Concession 11, for an alternate access to his cottage down the lane. The original survey showed a 20-foot right-of-way. The next step was to call in a surveyor who said he could not do it until the following season. Impatient to mark out our new territory, Sandy and I decided to get started on our own that fall.

I had plenty of experience as a land surveyor to rely on. My first job, after graduating from Ryerson in 1967, was as a plans-examiner with the Department of Energy Mines and Resources in Ottawa. Its Legal Surveys Branch was responsible for all land surveys on Indian Reserves, National Parks, Department of Transport lands and other Crown lands across Canada and in the northern territories. Survey crews were sent out every season for the field work. They were comprised of a Legal Surveyor, with appropriate provincial qualifications, or a Dominion Land Surveyor, along with a Party Chief, instrument-men, summer students and locally hired laborers. At the end of the season, they would settle in for the winter in Ottawa to complete their work and draw up their survey plans. There were many more survey requests than staff so much of the work was contracted out to local surveyors who submitted their plans for approval.

I was assigned to the plans-examination section, which was mainly comprised of old surveyors who had done their field service and were now settled into office work leading to retirement. Being an eager new recruit, with lots of energy and trying to impress, I was completing a survey plan review every week or two. One of the older fellows took me aside and told me to slow down or we would be out of work before the next survey returns came in.

I realized I was better suited for field work and asked for a transfer. Asked where I wanted to work, I thought that the most interesting challenge was the Arctic. The other surveyors were happy that I took that route as it was the least desired posting for the married men with families. The crew was sent north in May and did not return until October. There were no phones and the only contact with home was by radio-phone which was open to anyone with a short-wave radio, making private conversations impossible. Thirty years later, Sandy and I were sitting in a McDonalds at Walmart with an Inuit couple from Cape Dorset. Ooloosie's cell phone rang, she answered and said her son was calling on his satellite phone to report he had caught six fish. Times have certainly changed, both in communication and in survey practice.

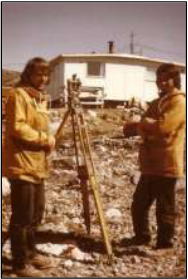

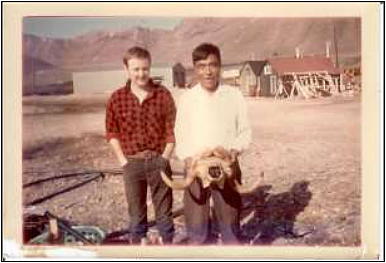

There were no hotels or grocery stores with fresh supplies in 1968. We slept in tents or in temporary bunks in school-houses and ate freeze-dried and canned food. There was no road access to the Arctic making flying to the remote communities an adventure. In spite of the hardships, it was an unforgettable experience in Canada's last frontier. Another benefit an old surveyor told me was that there was a girl behind every tree. When I got off the plane in Frobisher Bay, I saw there were no trees. This was actually a surveyor's dream posting since there are no trees and the 24-hour daylight in the land of the midnight sun allowed for long, productive days between chartered plane flights. I also developed a life-long love for the north country and for Inuit Art. I volunteered to go back for two other summers. Picture shows Gabe Aucoin and Ernie Bies at Cape Dorset in 1973.

Back to Sleepy Hollow Lane. Even though my surveying career ended in 1973, it was like riding a bike. You never forget. I still had some personal gear, like plumb-bobs, survey ribbon and chaining equipment stashed in the basement. For clarity, a chain is a holdover name for the long tape used for measuring the survey lines. Originally a chain was made up of 100 links and was 66 feet long. It dates back to land surveys in the 1600s and relates to measurements of the day. Modern metal chains come in lengths of 100, 200 and 300 feet.

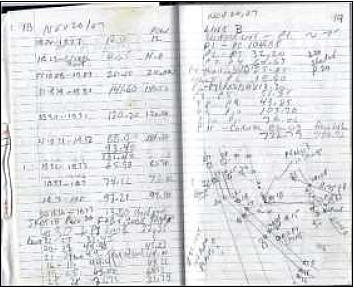

Land Titles in Pembroke provided the related survey plans for Sleepy Hollow Lane, and I was back in field survey mode. An old surveyor friend loaned me the equipment I needed, which consisted of a T1A Theodolite (transit), tripod and a bar-finder. A can of fluorescent spray paint and I was set to go. My wife, Sandy, proved to be a very competent assistant, plumb-bobbing with the best. With some minor training, she was soon shouting out survey commands, using the transit to produce line and holding her end of the chain. I bet when she married a surveyor in 1970, she never envisioned doing this 37 years later. In my day we had to clear all the trees and brush between survey stations, which I accomplished with my trusty Swedish axe. The first job was to locate existing survey posts which, thanks to the magical bar-finder, we did in record time. We found all but one of the 45 survey posts in the vicinity and along the lane. These were numbered and marked on our working sketch. I marked them all with 2x2 inch stakes and covered them with a flower pot and a rock which I sprayed with fluorescent orange paint.

I was in my glory, tramping through the bush like the 22-year-old rookie surveyor from forty-some years ago. I slept well but awoke before dawn every morning, waiting for the sun to come up, so I could get back out in the bush. Sandy was not quite so eager, insisting we have breakfast first.

Finding the location of the boundary line between Lots 26 and 27 was a challenge because there was no obvious evidence of the original fence-line. I had calculated the distance from the existing survey-posts at the lane, and sighted along the posts at the side of my current lot. Not finding the fence where it should be, I stood and pondered my next move only to realize I was standing on a perfectly squared moss-covered post, obviously man-made. Carefully removing the moss, I found the remnants of barbed wire. Looking left and right I saw evidence of stumps of trees and other fence posts and bits of wire. It was a eureka moment, like when I found 100-year-old cedar survey posts on Indian Reserve boundary surveys. Working with this bit of fence, I was able to find nearby survey posts for both the boundary and the original 20-foot road allowance.

Now we had to establish the new corners. The east corner was easy as I simply measured out the line and planted a 2x2 inch stake. The waterfront corner was a challenge as there was no connection to the nearby survey bars. Knowing that the line had to be 66 feet from the existing boundary posts along the lane, I laid out an offset line and proceeded to clear the brush in both directions. This line was 700 feet long in total. It was very gratifying to hit the 2x2 corner post that I had set at the east boundary. Close enough for my rough work.

I had kept extensive field notes and sketched a plan which I presented to the surveyor. When he came to

do the survey the next summer, he spent about two

hours on site. He examined a few of the bars I had found to satisfy himself

that they were undisturbed.

Then he laid out a control line on the lane and tied it in

to some of the existing bars. He had a fancy electronic

transit called a Total Station that did all the calculations

and recorded all the data for him. He did not use a

chain but his assistant had a target attached to a

plumb-bob string, that enabled the transit to

measure and record the distance. A Total Station is an optical

instrument used in modern surveying. It is a combination of an

electronic theodolite (transit), an electronic distance measuring

device (EDM) and software running on an external computer,

such as a laptop or data collector.

that they were undisturbed.

Then he laid out a control line on the lane and tied it in

to some of the existing bars. He had a fancy electronic

transit called a Total Station that did all the calculations

and recorded all the data for him. He did not use a

chain but his assistant had a target attached to a

plumb-bob string, that enabled the transit to

measure and record the distance. A Total Station is an optical

instrument used in modern surveying. It is a combination of an

electronic theodolite (transit), an electronic distance measuring

device (EDM) and software running on an external computer,

such as a laptop or data collector.

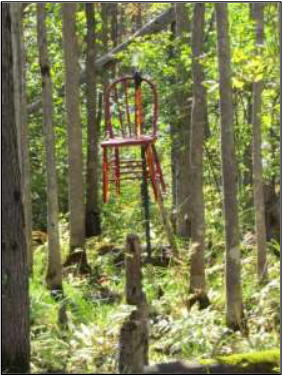

He returned the next day with the calculated distance for the two new bars he had to plant at either end of the added-on section of property. Later, I marked the new corner with a steel post and hung an abandoned red chair on it so I could see it from the road. Planting the two bars took less than an hour and, a week later, I had a preliminary survey plan that his wife plotted in their home office, using the data stored in the Total Station. Oh, and by the way, he told me that I didn't have to cut all those lines out as the electronics on his machine could get by with minimal clearing. But, being an old-school guy, I had the satisfaction of seeing the results of my work at the end of each day.

I will leave you with some reminiscences of my surveying days in the Arctic.

Marcussie: In 1968 our work brought us to Grise Fiord, which is the northernmost inhabited community in Canada. When we were there, we met the newly elected Prime Minister of Canada, Pierre Elliot Trudeau, who was making a tour of the Northwest Territories. Our survey involved laying out the lots for the existing houses and planned expansion, in an orderly manner and marking all the corners with survey bars. These consisted of 30-inch iron bars, threaded at one end to receive an aluminum cap, that we later inscribed with survey information, such as lot numbers and year of survey. They, in fact, resembled large nails that we drove into the ground with a sledge hammer. Keep in mind that Inuit, who were traditionally nomadic, did not have the same southern sense of land ownership as the community planners. They had no idea what we were even doing there. Marcussie would watch us every day and laugh uproariously. He spoke no English and I spoke no Inuktitut. Finally, RCMP Sergeant Dick Vit found out what the joke was. On asking Marcussie, he answered, "The White man must be crazy. The land has been here forever and he is trying to nail it down." A very sensible observation. Marcussie is pictured holding a Musk Ox Skull with local cook Findley Aird.

Mitty Finds a Tree: In 1972, when we were in Cape Dorset, Mitty, a pure-bred Siberian husky, had the run of the town. Remember, I said there were no trees. Mitty solved that problem by using the wooden tripod leg on our transit as an alternate tree to mark his territory. Bill Stretton was the surveyor in charge and he threw a rock at Mitty. This alpha male husky did not take that lying down. Biding his time, he followed us around, waiting for an opportunity. This came when Bill set his knapsack down, unattended, with the flap open. Mitty lined it up, lifted a leg and deposited a perfect stream into the knapsack, drenching the contents, including Bill's field-book and lunch. Mitty won that round.

Ernie and Sandy in Cape Dorset, 1973

Can you provide corrections or comments?

Please report technical issues to: